The mysterious affair at Sweeny Ranch

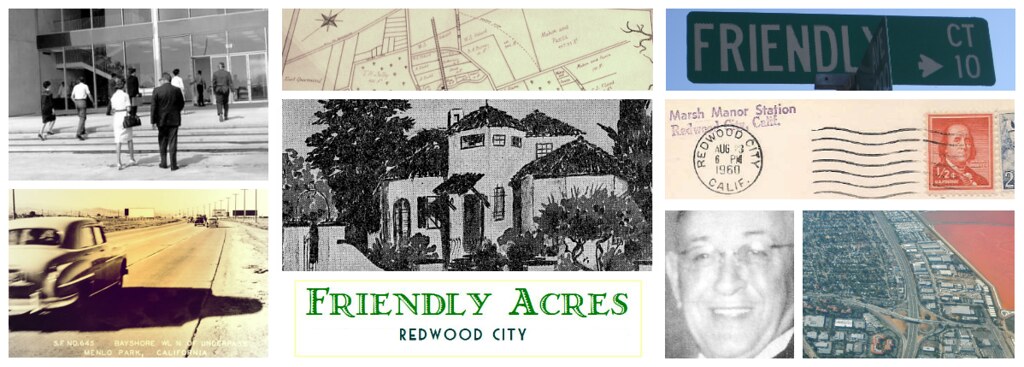

If you happen to visit the San Mateo County Archives, located in the courthouse in downtown Redwood City, you'll see that they have wonderful old maps of the Peninsula hanging on their walls and ensconced in their archive drawers. (1:1 Replica copies even for sale in the gift shop.) And if you look closely at the maps of the late 1800s and early 1900s, you'll discover that Friendly Acres, and the surrounding area, is a neighborhood that was carved out of a previous property formerly known as Sweeny Ranch, named after an Irish gentleman by the name of Myles Sweeny. Sweeny had bought the subdivided land from Timothy Guy Phelps who in turn had acquired the land from the Arguello estate - the Arguello's were the original spanish owners of Rancho de las Pulgas.Sweeny Ranch at that time was pastureland. Myles Sweeny had originally purchased the land and the adjoining marshes for harvesting grains, sheep and cattle farming, some horses, but also for duck hunting and for easy access to the bay for shipping of his import/export interests (read including liquor...). From the county maps of the period, the few buildings that existed on the Sweeny property were mostly farm buildings or barns. And the primary farm buildings were right behind where the Starbucks now stands on the corner of Bay Road and Marsh Road, just west of the railroad tracks, and where the houses now stand around Athlone Ct.

Initial investigation of the 'Sweeny'/'Sweeney' name, yielded a variety of records from the Schellens collection at the Redwood City Library History room, and the San Francisco Genealogical society. But one isolated entry stood out: It was a 1903 record in the San Mateo County Death Register for a Charles Brown who had apparently died at "Sweeney Ranch near Redwood City", of Strychnine poisoning.

- The location of death was at Sweeney Ranch. Did this mean he died inside the ranch building, or somewhere outside on the ranch or at another building on the ranch?

- Cause of death was Strychnine poisoning. This, admittedly, conjured a gasp of surprise - I hadn't read about strychnine poisoning since Agatha Christie. Was he murdered? (And if you've ever read any Agatha Christie books, viz. "The Mysterious Affair at Styles," first published in 1920, which involved homicidal use of said poison, your mind would have wandered in that direction too.)

- His name was Charles Brown. Was this the Searsville Charles Brown, or a son of? It turns out the Searsville Charles Brown, an early Bay Area entrepreneur, and founder of the now dam-engulfed town of Searsville, had died much earlier of natural causes, in 1885, was Swedish, and substantially older than our victim. Our fellow, from Sweeny Ranch, was originally from New York, according to the index entry and had died at age 55 in 1903. So no connection there. Curiously, though, both men were buried in the same graveyard, the Union Cemetery in Redwood City. The Coroner's Burial Register for Union Cemetery didn't yield any more information, other than the fact that one had a headstone, and the other didn't. Our chap ended up in the Paupers' Grave, alongside other John and Jane Does. And the Union Cemetery archives appeared to have no biography on our man.

| Source: Burial Register Union Cemetery Archives, Redwood City, CA |

In the rush of gold fever, thousands upon thousands of men migrated west in the 1840s, only to realize that it was hard, back-breaking work, highly competitive, dangerous and the odds of striking lucky in gold country with a large nugget payoff were poor. Many turned instead to other jobs - which were already in scant supply due to competition from the large influx of male immigrants.

Eight years later, age 33, Brown is listed as a laborer, boarding at Victoriano Guerrero's house near Pillar Point. This was no mean feat to be lodging at Victoriano Guerrero's house - especially if he was possibly working there too.

|

| Victoriano Guerrero's House, Pillar Point, San Mateo Co. |

For whatever reason, Charles Brown did not stay on at the Guerrero ranch. He didn't become a rancher but remained a ranch hand. He moved to Belmont, and then to Redwood City and appears to have been a dairyman farmer, finally working at James Curran's farm which pastured its stock on the Sweeny Ranch lands. But his position at the Curran Ranch, where he may have been working as a cook for as long as three years prior to his death, is surprising.

So what was Brown doing as a cook on Sweeny Ranch? A profession held by many chinese immigrants, (even Mrs. Leland Stanford's cook was chinese). And what a horrible, but exotic way to go. Strychnine?

Death by poison has been recorded since the earliest times. Indeed, Cleopatra's regal death was from asp venom; and the venerable Socrates by hemlock. While today, it is not common to hear about deaths from venom, in the early 1900s deaths by poison were really all the rage!

It wasn't until 1818 when strychnine was extracted as an alkaloid, by two French chemists, Joseph Bienaimé Caventou and Pierre-Joseph Pelletier, that its manufacture, marketing and distribution exploded. This was a time when the field of chemistry and extractions of poisonous alkaloids for medicinal and industrial purposes flourished; and it was a time when there were more recorded deaths by poison than at any other period in known history. So its with good reason that historians and chemists call the 1800s thru to the early 1900s the golden age of poisoning.

As the 1900s rolled out, strychnine became widely available in cathartic pill form. It was popularly prescribed in small doses, as a digestive aid to reduce stomach acid, and as a palliative for stomach ulcers. But not surprisingly, the self-medication caused a significant number of fatalities from unintended suicide and ingestions throughout the country (and most of the western world).

A small bottle of strychnine powder would have been kept on a kitchen shelf, or under the kitchen sink, or in a medicine cabinet, or even bedside table - and its certainly not difficult to see the attraction that a little bottle presents to the eyes and hands of a curious child. Strychnine rapidly gained notoriety as a major cause of toxicologic death in children, especially in the early 1900s. Indeed the attraction of small bottles to small hands remains true today. But in 1903 the surgeon general's warning of "Keep Out of the Reach of Children" had not as yet been conceived.

We know that medicine bottles from early 20th century Redwood City druggists were usually embossed glass so it was fairly easy to feel, as well as see, what you were holding. But why keep such a toxic poison as strychnine so close to the kitchen pantry or bedside table, when its properties were well known?

|

| Vintage embossed bottles - all from the Pioneer Drug Store in Redwood City |

Its highly likely that people kept strychnine as a pesticide against vermin. On a rural farm, like Sweeny Ranch which was surrounded by hay fields, it would have been a common household and farm item.

Early European settlers to America already brought knowledge of strychnine with them well before the 19th century French chemists came up with their extract. In fact, the ground seeds from the Strychnos nux vomica tree, an East Indian tree, were known to be used as a rodenticide as early as the 16th century in Germany.

Was the strychnine poison that killed Charles Brown from a pesticide bottle? or from a medicinal household/bedside bottle? Doses would have been different, depending on the use. It could also have been a general purpose bottle intended both for human self-medication and as pest-control?

Perhaps what is most telling in this story is that Brown's death in March 1903 happened to fall right in the middle of the greatest Rat Hunt in North American history.

By the end of the 19th century the chinese in Northern California had cornered the service industry, laundry and cooking, sewing and mending - juggling five or six jobs in a day, with very little sleep. Many of the European immigrants simply could not compete with the low wages and work ethic of the asian community. Resentment and racism bubbled up, particularly in San Francisco. And Northern California Labor Reformers were intent on curbing chinese immigration.

Racist anti-Chinese propaganda was about to succumb to mass hysteria: On New Year's Day of 1900, the plague quietly sailed into the port of San Francisco, aboard a steamship called the Australia.

The steamship was carrying a load of passengers, from HongKong and Honolulu where the plague had recently touched down. It also carried mail and some stowaway rats. The passengers arriving from the Orient were quarantined but the rats scuttled out true to their landlubber nature.

At the time, people hadn't yet made the correlation of rats and plague. But they were about to soon enough. Rodenticides containing Strychnine, Carbolic acid, and Arsenic became a common part of every household's arsenal of WMDs against The Rat.

'Rough on Rats' was an arsenic-based product developed in New Jersey in 1872 by a man named Ephraim Wells who came up with his own home-made concoction to eliminate rats. His wife jokingly called the recipe "Rough on Rats" and the product became a commercial success by word of mouth. Wells was also the creator of the advertizing, using his own imaginative drawings as artwork.

Ephraim Wells was an astute business man, and such was the popularity of his product that before the advent of the radio, gramophone or television, Rough on Rats even had its own marketing jingle and in 1882 they were even selling sheet music of the song composed for piano and 4-part voice. (The Library of Congress has a copy of the sheet music.)

The plague's provenance from China simply threw the hysteria of racist slurs and propaganda over the edge.

Its interesting to note that while east coast advertising showed whimsical ads of frustrated cats and little rats, squirrels and assorted bugs being tutored on how to avoid Rough on Rats, the West coast ads displayed a racial disparagement of the Chinese, most notably showing a chinese man eating a rat with the slogan "They must go" positioned immediately above the chinese man's head. Shocking by today's standards.

The efficacy of pesticide use was such that by 1910 the Federal Government had even bought 3600 boxes of Rough on Rats for use in the Panama Canal zone.

Rough on Rats continues in production today, no longer using the same arsenic base, and is the oldest U.S. rat-controlled-product trademark.

A tangential postscript to the Charles Brown story is a similar tale that befell Jane Stanford, wife of Leland Stanford, of University fame, who died 2 years after Charles Brown, in 1905, in Honolulu, allegedly from strychnine poisoning, in equally mysterious but more controversial circumstances.

In the month prior to her death, while she was still in San Francisco, Mrs. Stanford had consumed a glass of spring water which she noted had a bitter taste. Being paranoid that somebody might want to murder her because of her wealth, and suspecting foul play, she had the water tested. Chemical tests revealed a lethal amount of strychnine in the water. Her personal maid was fired.

Suffering from a cold and fatigued by the paranoia of being a target on someone's hit list, Jane Stanford decided to travel to Hawaii and then go on to Japan. Three or four weeks later, while on vacation in Oahu, Jane took a dose of bicarbonate of soda, popular remedy which she used frequently. Bertha Berner, her personal secretary of over 20 years, reported that, before dying, Mrs Stanford declared that she had been poisoned.

Trace amounts of strychnine were found in her body and in her bottle of bicarbonate. Her murderer was never conclusively determined. Although Ms. Berner, who was also a suspect, conveniently pointed blame at the chinese cook, Ah Wing, there were many who wanted Jane Stanford out of the way, including administrators of the University - who conveniently hushed up her murder.

Both Charles Brown and Mrs Stanford suffered the same excruciating death. Mrs Stanford's case was deliberate. But Brown's death is more if a mystery. His obit indicated that he committed suicide - "no reason can be found for his act excepting that Brown was at times a hard drinker and frequently indulged in sprees". Maybe he was drunk and consumed the bottle of strychnine thinking it was alcohol or bicarb? Or maybe there was foul play - possibly someone couldn't stand his cooking? Or wanted his job? Or maybe somebody wanted his house, land and assets? And wanted him out of the way, since he had no relatives, spouse or children? Foul play or accidental death? We will never know.

|

| Redwood City Democrat, March 26 1903 |

Charles Brown was buried in the Potter's Grave section of Union Cemetery in Redwood City, resting there until the 21st century as an unknown body with no headstone. But we now have his name and an extra biography to add to the stories of those at Union Cemetery. We can even paint a picture of what he looked like: 5'5 and 3/4" in height, brown hair, of dark complexion, with gray eyes. A Laborer. Ranch hand. Dairyman. Farmer. Cook.

Charles Brown

Born 30 May 1848.

Died 24 March 1903.

R.I.P.

-----------------

References

[1] The number of strychnine exposures in the United States has fallen significantly since its elimination from nonprescription preparations in 1962. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/strychnine-poisoning#H1, Kavita M. Babu M.D.

[2] Jane Stanford biography: See Stanford website - http://janestanford.stanford.edu/biography.html

[3] Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco, Marilyn Chase. http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/169911-1

[4] The Cat Made Me Buy It!, Alice Muncaster, 1984, Three Rivers Press - 116 full-color photographs of cats appearing in scores of different ads and promotions created over the last century.

[5] Redwood City Union Cemetery Archives http://www.historicunioncemetery.com/Archives.php

[6] Library of Congress http://www.historicunioncemetery.com/Archives.php

[7] Newspaper article on arrests made in Jane Stanford murder: San Francisco Call, Vol 97, No. 94, 3 March 1905. http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC19050303.2.2#

[8] Charles Brown Obituary - Redwood City Democrat Newspaper, 26 March 1903. Newspaper Archive held in the Karl A. Vollmayer Local History Room, Redwood City Library, Redwood City. City: http://redwoodcityhistoryroom.com/

[9[ Photo and history of Victoriano Guerrero house, at "Remembering the [Rancho] Corral de Tierra": http://www.halfmoonbaymemories.com/?p=8793

[10] San Mateo County Voter Registrations